I think Roald Dahl was the first author who I actively sought out as a kid. It was he and Judy Blume that I voraciously read as a child. Matilda remains one of my favorite books of all time.

Puffin publishing recently announced that, in collaboration with Netflix (who owns the rights to the Roald Dahl novels) and “Inclusive Readers”, have changed various parts of the language of several Roald Dahl’s children’s novels.

The goal of the changes was to promote more inclusive language. Among the changes were the elimination of the word “fat” to describe characters like Augustus Gloop. Instead of fat, now Augustus is “enormous.”

I believe that changing the writer’s words is a mistake. I think this is a bad move by Netflix and Puffin publishing. But I don’t want to focus on the politics of the changing. Lots of people have already commented on the “woke PC police gone amok” and the idea of the Ministry of Truth coming in to change history to suit Big Brother’s current needs.

I share those concerns to a great extent. But that is not what I want to discuss. I would like instead to focus on what I believe are the unintended consequences of trying to completely prevent kids from being exposed to potential harm.

Peanut Butter

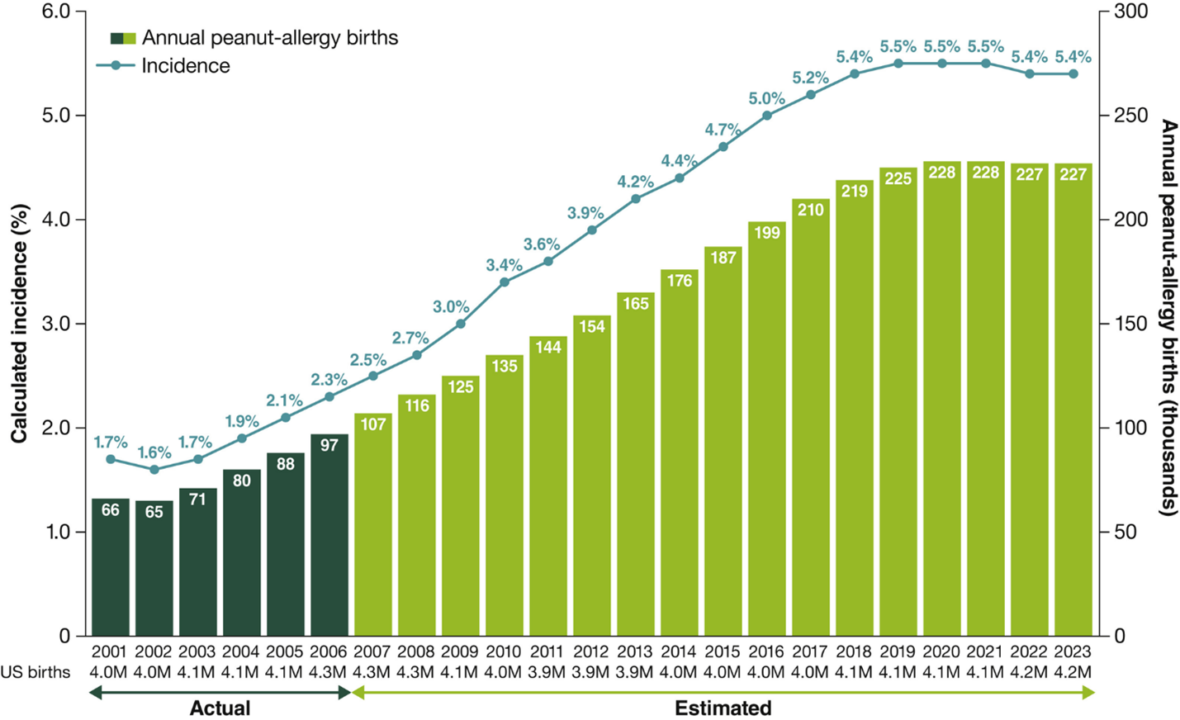

Schools in America have been placing various levels of restrictions on kids consuming peanut butter and nut-related foods since about 2006-2007.

Incidence of peanut allergies in the United States have tripled since the peanut ban was placed in schools. Today it is estimated that between 2.5 – 5% of the US population might have a peanut allergy.

The growth in peanut allergies seems to coincide with schools, to protect children, banning peanuts in schools. The American Medical Association recommended children avoiding consuming peanuts as a potential allergen around 2005. As schools have banned peanuts kids have eaten less peanuts. This has led to a cycle; parents don’t feed their kids peanuts because they have heard, overtly or vaguely, that they shouldn’t feed their kids peanuts. By not exposing their little kids to peanuts they have created the conditions by which the immune system overreacts to peanut exposure.

So. to protect children from developing allergies we implemented a policy that tripled the rate of allergic reactions. The American Medical Association recently reversed its recommendation and now suggest that children eat peanuts at an earlier age.

When Protecting Children Harms Them

I think the peanut allergy story highlights something that is worth exploring and extrapolating beyond its original issue.

Whenever we attempt to minimize the perceived risk of some issue through some big policy, we risk creating ripple effects that we cannot easily predict. More often than we would care to admit, whenever we try too hard to protect people from making choices, we wind up doing more harm than good.

Changing books is analogous to recommending a ban on peanut butter. The proposed solution to reducing risk is to try and eliminate exposure to either perceived harmful words, ideas or character of the author. The problem with eliminating exposure is that just as there were unintended consequences to banning peanut butter there will likely be unintended consequences to changing books.

Is there an alternative to completely changing his books?

How Israel Handles Peanuts

I was told by a coworker that “Bamba”, an Israeli peanut-based candy, is so loved that it is anecdotally the third most common word an Israeli baby learns. It is also the most likely reason that Israeli children rarely develop peanut allergies.

Israeli kids have peanut allergies at less than 1/10th the rate of North American kids. It could be that there are genetic differences but what is more likely is that the immune system of Israeli children learns to not overreact to the peanut allergens the way that kids who are introduced to the allergens later in life.

Introducing kids, or at least giving them the option to explore, to things that might potentially cause mild discomfort seems to be a better strategy for long term health and wellbeing of kids.

This seems like the right strategy for exposing kids to lots of potentially difficult things; low doses of exposure, which helps the body become acclimated to the potential allergen so that the immune system can develop the kind of strength it needs to handle the allergen.

Kids exposed to peanuts at an early age can eat more things without fear. They can try new and interesting foods. They can explore culinary interests. Kids with peanut allergies need to be careful; they rarely can be adventurous with their eating out of worry of a potential allergic reaction.

Similarly, kids who are exposed to books where people are rude and insulting and use terms that we currently call “microaggressions” will be more likely to have the fortitude to handle the stress of encountering those words in real life than kids who have been sheltered from mean words and thoughts. I often marvel at how much more fragile kids seem compared to kids of my generation. Depression levels among teenagers today are significantly higher than they were even a decade ago. I’m sure that is due to a variety of factors; obsessive use of social media and covid lockdowns being two of the major factors that come to mind.

But ultimately, I think a large part of that fragility comes from the lack of being pushed and tested past comfort zones. As a society we have collectively attempted to shield children from a lot of challenges. This has made teenagers collectively weaker and less capable of independently solving problems in my opinion.

Reconciling Roald Dahl’s Antisemitism

It wasn’t until I started doing research for this essay that I learned about Roald Dahl’s horrible personality and his antisemitic remarks. How do you reconcile the joyous and wonderful books he wrote with the terrible ideas he espoused? Knowing about that side of his personality reinforces the old saying “never meet your heroes”.

Under the circumstances I completely understand why some people might not want their kids to read Roald Dahl. I might not agree with that approach, but I can certainly understand that impulse.

If Israel followed the American approach of eliminating exposure, then there would presumably be an effort to strongly discourage Roald Dahl’s books from being sold. But there does not seem to be a collective movement to get rid of Dahl’s books in Israel. I could be mistaken but the general impression I got from discussing this issue with coworkers at the orthodox Jewish school where I teach, many who are Israeli, was the general sentiment that they could separate the art from the artist.

In general, I think the US could learn to apply the Israeli approach – allow for controlled exposure to risk and allow children to become stronger to meet the challenge rather than trying to eliminate all potential risk. There seems to be a greater strength and resilience that arises when people learn to overcome something rather than trying to completely prevent the exposure.

Selim Tlili teaches biology at the Ramaz School, a private orthodox Jewish school in Manhattan. He received his bachelors in biology at SUNY Geneseo and his Masters in Public Health from Hunter College. Subscribe to his writing about education, literature and self improvement at Selim.Digital